The mystery of why Tyrannosaurs – and Tyrannosaurus rex in particular – had such tiny arms, has been a focal point of paleontological discussions for going on a century now. And let’s not get started on the endless list of T-Rex Tiny Arms memes that pervade the web, mocking the poor “Tyrant lizard king” for his “shortcomings” . . . ouch.

But

Why did T-Rex have such small arms? They certainly weren’t good weapons, despite their relative strength. Many explanations have been offered over the decades, including the arms not being needed due to the size and power of the animal’s mouth, or that they were relegated to minor tasks such as picking its teeth, helping it raise itself erect, or as pelvic/mating spurs, as seen on some of today’s more primitive snakes.

Theories about “T-Rex Tiny Arms”

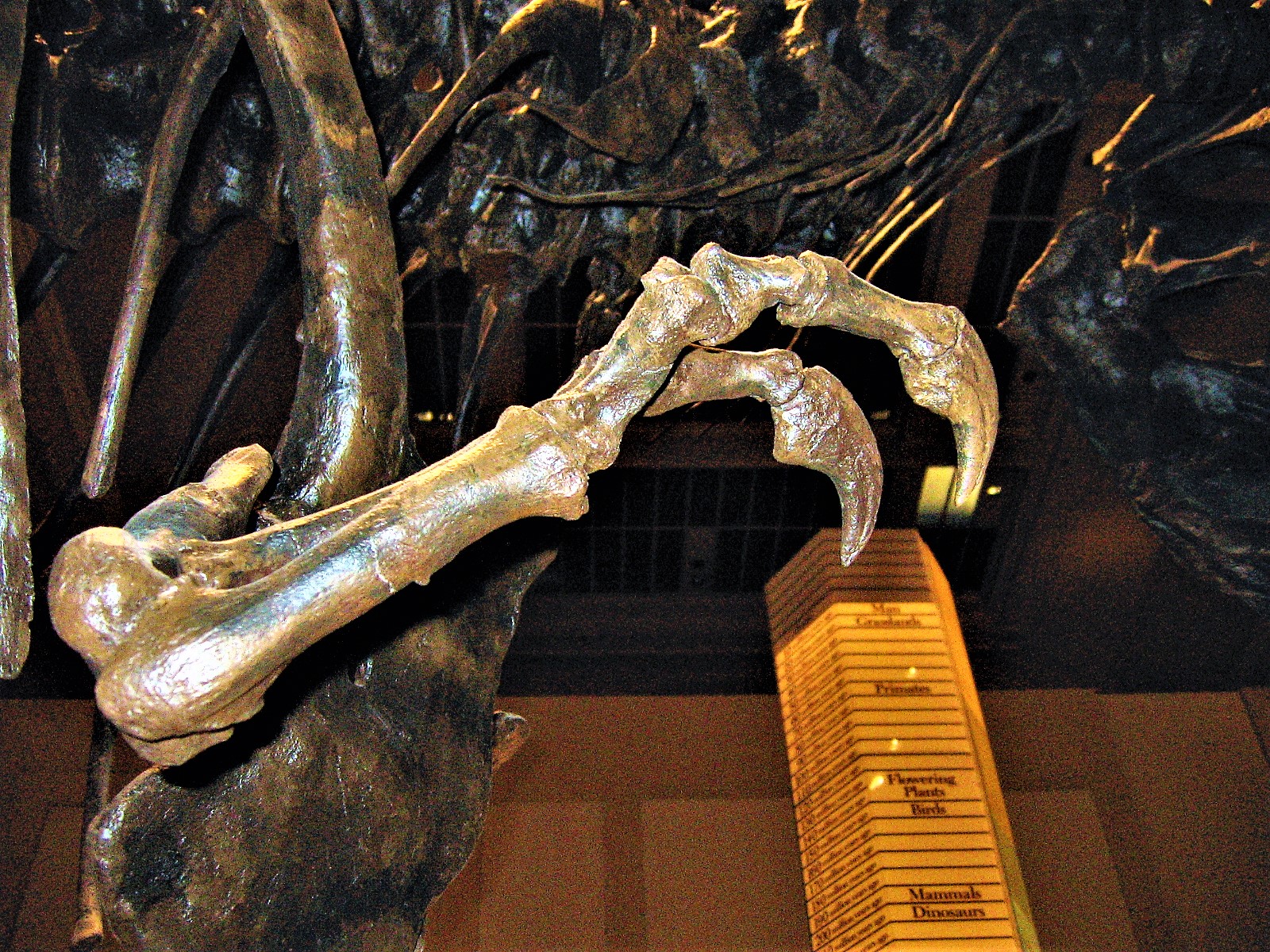

I’m going to address some of those theories succinctly, and also offer my own opinion as to the reason behind such diminutive front limbs on such a huge and mighty hunter. As a toothpick, I can see the arms being useful. If a tyrannosaur could lower its head enough to reach its vast array of dentition, extracting an annoying piece of bone with it’s stubby, two-clawed (three, if we count the vestigial third one) hand would make sense.

But that would be a bonus,

like you or I scratching ourselves, and definitely not the reduced limb’s primary purpose. And mating spurs, although not discounted, don’t make a lot of sense. As I pointed out to a well-known paleontologist recently (while we discussed the reduced hind limbs of sea turtles, as pertains to my theory on plesiosaur locomotion), both male and female turtles have them.

This basically negated his opinion that the hind limbs were used solely for excavating nests. If that were true, why would the male sea turtles have reduced, and sometimes larger, hind limbs as well? No, they were used mainly for steering, as rudders, and secondarily as excavators for digging out one’s nursery. The same thing applies to T-Rex. Both males and females have the same shortened front limbs, so any notion of mating spurs is contraindicated.

Helping the animal to hoist itself erect does have some merit, however. Despite some individuals dismissing the notion, stating that the limbs were too small and not strong enough, I beg to differ. Although, as I will explain shortly, the limbs did not evolve to become shorter for this reason, I believe the reason they maintained their considerable strength and muscular mass was to continue to allow them to help T-Rex get to its feet from a resting position.

It’s been documented that a tyrannosaur’s arms were incredibly powerful, with each bicep conservatively estimated at being able to curl at least 430 lbs. I’d like to know more about the power of the animal’s triceps – an aspect of its arm strength that science has, to the best of my knowledge, yet to explore.

In humans, the triceps (pushing muscles) are typically far stronger than the biceps. Using myself as an example, in my “heyday”, at a lean 190 lbs. and standing 6’1” tall, I was able to curl, with proper form, 185 lbs. using an Olympic bar for a single quality rep. However, while doing triceps presses between two benches, I could do my body-weight, plus 5 additional 45 lb. Olympic plates (225 lbs.) stacked on my lap, for ten reps easy.

That’s a combined weight of well over 400 lbs. for sets. For a single rep, I probably could’ve generated at least 500 lbs. of force. That said, and using round figures, if a T-Rex was capable of curling, say, 1,000 pounds using both arms, it could probably chest press 3,000 lbs. for sets. And much more – possibly as much as 4,000 or even 5,000 lbs. for a single, explosive push.

With the animal, itself, weighing somewhere in the 9-15-ton range (current estimates), even lifting 5,000 pounds doesn’t seem like much. But when the huge theropod was resting with its chest on the ground, and suddenly decided to rouse itself, the forelimbs weren’t forced to hoist the entire front portion of its body (3-5-tons on a guess) by themselves.

Most of that work was done by the immensely powerful muscles of the thigh and back, and counterbalanced by, and even receiving pull from, the massive muscles of the tail. But, a sudden shove from the forelimbs that generated say, a ton or two of thrust, would certainly have helped to get the animal moving, and would have made getting to its feet that much easier. Think of yourself rising from a chair and giving the chair arms a push with your palms to get things going.

Why T-Rex Had Tiny Arms

That said, I think we can safely conclude that T-rex small arms were still powerful and could be used to help it stand. But the question about T-rex Tiny Arms remains, why did they get so small in the first place? Why did they evolve to become the stunted powerhouses that they were? The answer is, IMHO, evolution adaptations as relates to prey, including the choice of primary prey, and how that prey was to be brought down.

1. Lethal bite

First, let’s discuss weaponry. Tyrannosaurs didn’t need forelimbs to help them hunt. Unlike Allosaurus, with its comparatively smaller head and weaker jaws, but backed by large and powerful front limbs, equipped with long, hooked talons, T-Rex’s head was enormous and the most powerful bite of any known terrestrial carnivore (possible exception of semi-aquatic extinct crocodilians). Does an Orca, crocodile, or Komodo dragon need front limbs to seize its prey while it hunts? How about a great white shark, mosasaur, Livyatan, or Megalodon? No. All of these animals rely or relied on one thing – a lethal bite. And unlike “T-Rex’s bite” was astonishing; it didn’t need to do slashing attacks like the Carcharodontosauridae did with sauropods, waiting for them to bleed out; it was able to punch through bone, pulverizing vertebrae – maybe even crushing the necks of its prey, and stopping them in their tracks.

2. Speed

Another fact just like T-Rex Tiny Arms, he also didn’t have Allosaurus fragilis’s speed or agility. It was built more like a tank. So, it wasn’t topping out at 35 mph, (some estimates put it at 18 mph maximum or even 11) but it didn’t need to; it only needed to be fast enough to catch its prey. And what was its prey? Early, smallish tyrannosaurs like Kileskus and Raptorex were lighter, faster, and had larger forelimbs. As a result, they preyed on a variety of prey items.

But as the Tyrannosauridae came into their own, and with the rise of such animals as Appalachiosaurus, Gorgosaurus, and Albertosaurus, their bodies and heads grew, while their front limbs shrank. They fed on an assortment of dinosaurs, including hadrosaurs and ankylosaurs, but a high percentage of their protein came from ceratopsians of assorted species.

In the case of T-Rex, the last and greatest of the Tyrannosauridae, this included the world-famous Triceratops. These animals were the American bison of their day, and some believe that vast herds of them once roamed North America – as wildebeests do in present-day Africa. They are hunted by lions. And what was the lion of the Cretaceous? Tyrannosaurus rex.

3. A Risk To The Predator

Now, this is where things get interesting. The problem with hunting huge and heavy horned dinosaurs are their horns. These animals, with their bony frills protecting their most vulnerable part – their neck – were undoubtedly aggressive defenders, possibly even using a group dynamic, “circling the wagons” like extant musk ox. But regardless, even one-on-one, a battle with an adult Triceratops, or an evenly matched ceratopsian of any species, would have been a gladiatorial match of epic proportions, and likely to the death. And this is where T-Rex tiny arms came into play.

A picture of a T-Rex/Triceratops match-up brings things quickly into focus. The Tyrannosaur advances cautiously, trying to get around its opponent’s defenses – that bony shield and those spear-like horns. But unless caught unawares, the Triceratops will continue to keep its weaponry pointed at its adversary, which leaves T-Rex with the option of trying to seize the shield itself (this is where those armor-piercing teeth excel) and trying to grapple with the ceratopsian in an effort to take it to the ground. If two or more of the huge theropods were working in cahoots, and if the rest of the Triceratops herd was spooked and inclined to abandon an individual, as Cape buffalo sometimes do when attacked by lions, that would work to the Predators’ favor.

But regardless,

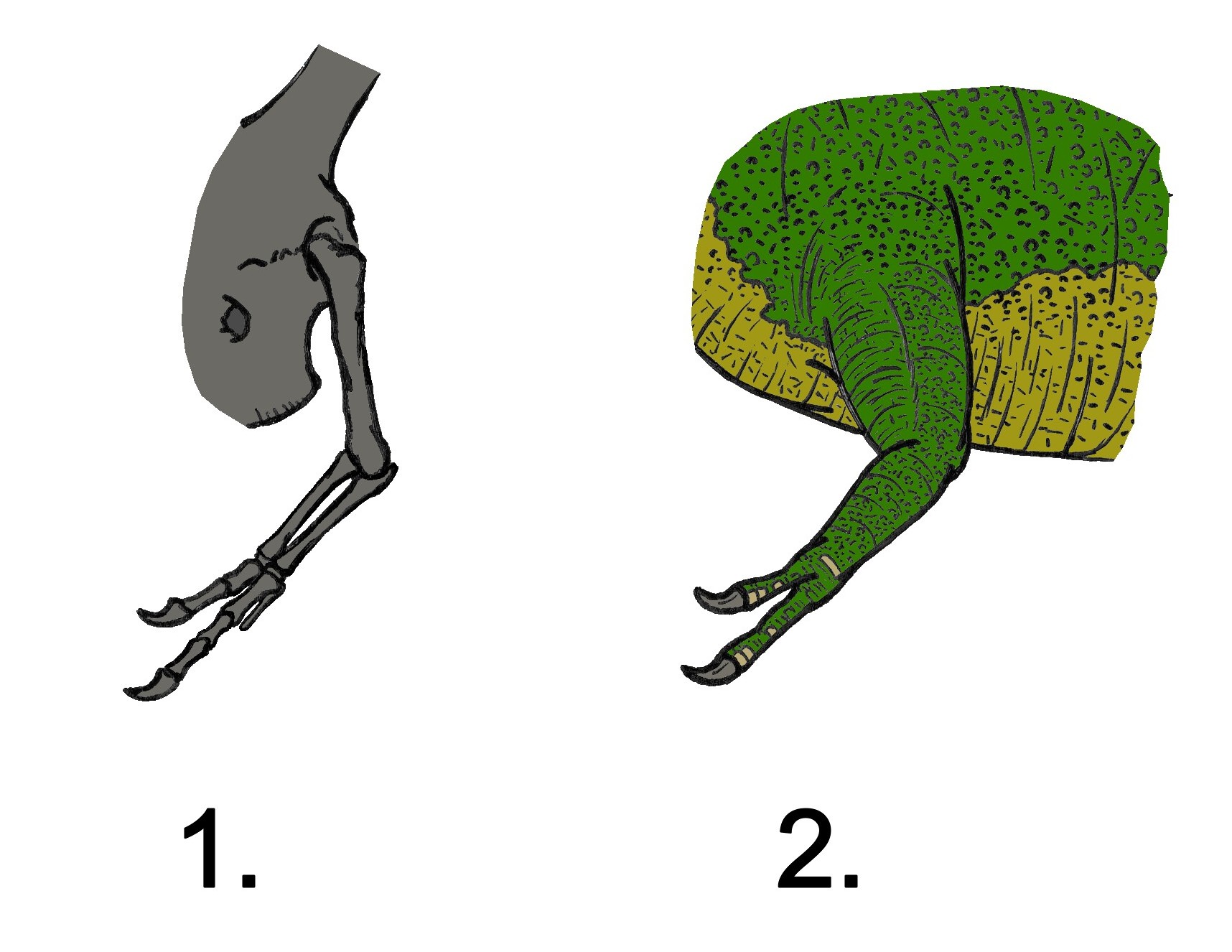

the Rex still has to focus on bypassing the Triceratops’s horns before it can make its move. And it has to protect its chest while doing so. With its superior size, height, and reach advantage, and exercising caution and retreating as needed, it’s able to keep its body out of harm’s way – for the most part. However, if its arms were larger, like those of an Allosaurs, for example, they would pose an added risk to the predator. Should a Triceratops manage to puncture one of those arms, the Rex could suffer a severe wound, possibly even a mortal one.

But, worse, should the ceratopsian torque its head sideways, as they may well have done when defending themselves, the Tyrannosaur, with one of its arms already speared through, is now at risk of being yanked sideways and crashing to the ground.

An impact like that would be damaging, in and of itself, but worse, it would allow an aggressive triceratops the chance to rush in, impaling its attacker like an elephant does with its tusks. The wounds received from such a charge could easily have been fatal. Let us also keep in mind, that goring alone wasn’t the sole danger facing any Tyrannosaur when attacking a ceratopsian. Any animal will bite when fighting for its life, even a rabbit. In this case, horned dinosaurs were equipped with large, shearing jaws that could have done significant damage in a life-or-death confrontation. Especially, against a vulnerable forelimb. So T-Rex Tiny arms do come handy :).

So, as dangerous as the nasal horn of Styracosaurus was, or the brow horns of an adult Torosaurus, even a seemingly less well-armed Pachyrhinosaurus or Chasmosaurus, for example, when grappled with, was capable of seizing a Tyrannosaur by the arm and taking it to the ground in a similar manner. And, like most boxers, once off its feet and struggling to rise, the embattled predator was vulnerable to attack – in this case, being rammed, gored, trampled, and/or bludgeoned.

So we don’t need a T-rex with long arms in this situation.

Conclusion

And this, IMHO, is why evolution caused the T-Rex’s, or any Tyrannosaurs, arms to shrink. We see this tendency toward forelimb reduction as the animals gradually grew in body size over millions of years, and as their choices of prey – including a focus on readily available ceratopsians – became more apparent. It shows in early forms like Xiongguanlong, before it split off from the main branch of the Tyrannosauridae, and becomes more apparent in larger species, like the early Cretaceous killer Yutyrannus, until it reaches its pinnacle in more familiar species like Daspletosaurus and good old Tyrannosaurus rex.

Think of it as a defensive strategy. Tucked in close to the body, the theropods’ vulnerable arms were effectively removed as incidental targets during combat with horned dinosaurs. Over time, Tyrannosaurs with stubbier arms fared better than their longer-armed brethren and survived to pass on their genes. This gradually resulted in smaller and smaller front limbs for the species in general. Although shorter, the arms still retained power to assist the animal in rising, and possibly in other, secondary manners, like “flossing” and mating, but mainly, they shrank because they were a risk to the predator during predator-prey interaction. Lastly, as an added bonus, the diminution of the front limbs, and the resultant reduction of its overall front end mass, most likely enabled the animal’s skull to further increase in mass, making the head bigger and its bite even more lethal as the arms got smaller.

And that’s my take on “T-Rex Tiny Arms” and why Tyrannosaurus rex wasn’t built like the strong-armed “Indominus rex” from “Jurassic World.” With its huge head and lethal bite, it was the land shark of its day. It didn’t have big arms because it didn’t need them, and, in fact, long (and vulnerable) arms would have been a detriment to it.

I’m Max Hawthorne, and I approve this message ? Thanks for stopping by.

If you haven’t done so yet,

Make sure you place your order for my latest novel, KRONOS RISING: KRAKEN (volume 2), book 5 in the Kronos Rising series.

Now available for presale on Amazon: Kronos Rising: Kraken vol. 2 presale link