What was the largest Russian pliosaur and when did it live?

Pliosaurs were a group of extinct macropredatory marine reptiles that lived from the Middle Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous Period. Although, by the end of the Jurassic, they had experienced a reduction in terms of both species’ diversity and overall body size, some very impressive forms still existed. Let’s take a look at a few of them, and see if a single pliosaur bone from an unexpected location can be used to not only identify one of these extinct apex predators, but also confirm that the species’ range was far greater than previously thought.

Who were the top predators of the Cretaceous seas?

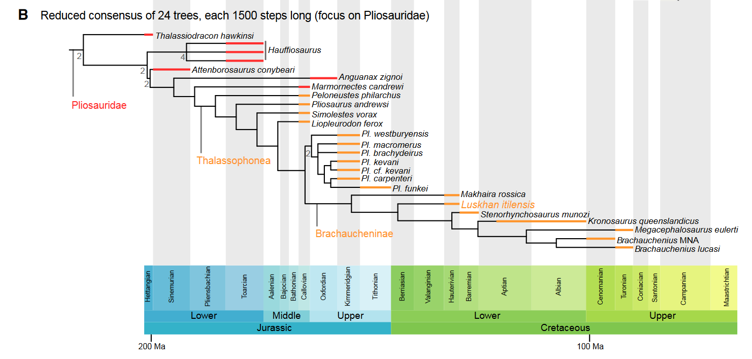

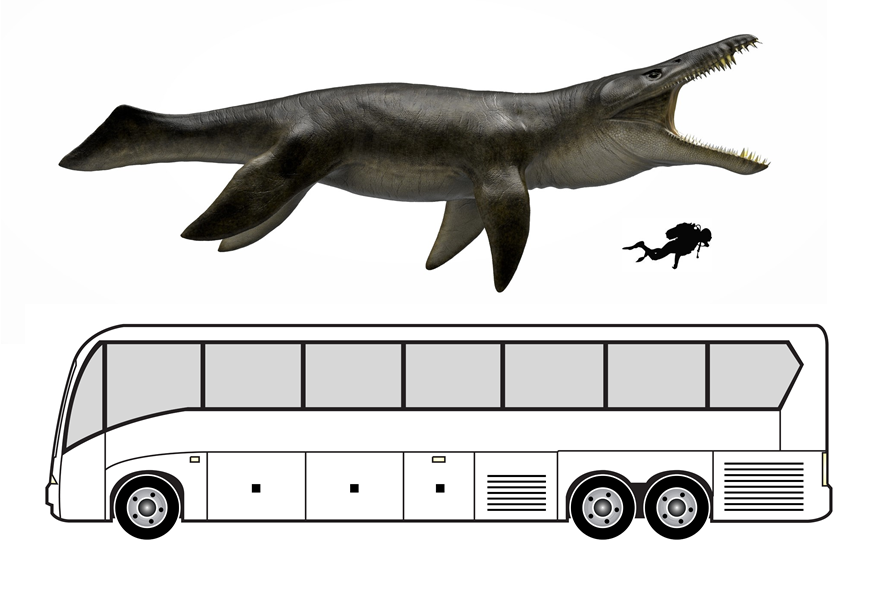

Before their extinction allowed mosasaurs to fill their ecological niche, species of pliosaur were the dominant predators of both Jurassic and Cretaceous marine ecosystems. Among the better known Cretaceous pliosaurids were the members of the sub-family Brachaucheninae, which included the macropredatory forms Kronosaurus queenslandicus and Kronosaurus boyacensis. Kronosaurus lived during the Early Cretaceous, from the Aptian to late Albian stages (approx. 125 to 100 million years ago). They are currently estimated to have reached up to 36 feet in length and 13+ tons, with huge skulls that made up as much as 25% of their total body length.

A bigger and badder predator.

Probably even larger than the two species of Kronosaurus was the recently discovered Sachicasaurus vitae, another brachauchenine pliosaur from the Barremian age of the Early Cretaceous (129.4 ± 1.5 million years ago and 125.0 ± 1.0 MYA). Sachicasaurus is known solely from the type specimen, which measured almost 35 feet in length, sans the majority of its tail, and had a skull just under nine feet in length. Earlier species of pliosaur had proportionately smaller skulls compared to body size and, with its missing caudal vertebrae, the animal might have reached 40 feet in length. Interestingly, and per its discoverers, it was a confirmed juvenile.

How big an adult of this species could have gotten remains to be seen, but it is quite possible that Sachicasaurus may have rivaled or even exceeded better-known Jurassic giants such as Pliosaurus macromerus in size. Based on its anatomy (flipper and skull size, and body ratios), I suspect that Sachicasaurus may have been a forerunner to, if not a direct ancestor of, Kronosaurus. If that is true, that would make it a chronospecies (no pun intended). Time will tell (again, no pun intended) if that turns out to be the case.

Such few fossils to work with!

One of the most frustrating things about pliosaur research is the ongoing lack of fossil material. Lucklessly for paleo-enthusiasts, these were animals that preferred the open sea and, as a result, many species are known from nothing but fragmentary remains. Consider Pliosaurus kevani, which was evaluated from just a skull, or Polyptychodon, whose entire existence was centered around the discovery of a single tooth (now considered nomen dubium per a 2016 review). Calculating proportions based on such remains is extremely difficult. Moreover, it’s virtually impossible to assign a species’ maximum size based on a single specimen, let alone a largely incomplete one. That would be like you or I walking along a stretch of dried riverbed 100 million years in the future and coming across a partial skull of a (presumably extinct) Nile crocodile, and deciding that, based on that specimen, that was as big as they got. It’s common knowledge that Nile crocs grow to 20+ feet at times, but the average specimen, depending on age and gender, is much smaller. That said, and taking into account how many crocs were (are) alive at any given moment, and multiplying that number by the millions of years the species existed, the odds of us happening to stumble onto a fossil from a 20-foot monster would be astronomically low. The same applies to virtually all prehistoric life.

A unique fossil.

I have a rare pliosaur fossil in my collection that bears investigating. It’s a perfectly preserved paddle bone measuring 3.5” in diameter that comes from the famous Kursk osteolite bone beds, near the city of Stary Oskol, Belogord Oblast, Russia (384 miles south of Moscow). It is from the Upper Albian period of the Cretaceous. 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma to 100.5 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). In terms of specifics, and after talking to paleontologists Valentin Fischer and Paul de la Salle, who provided feedback on both its morphology, as well as pointing out its large cell structure, the conclusion is that it’s definitely from a member of the pliosauridae. In addition, the bone itself is most likely a metapodial, probably #1 (assigning it to a front or rear paddle is difficult). With at least that information in hand, my next step is to try and determine the species of my Russian pliosaur and, lastly, to give an approximation of its size.

Pliosaur metapodial (image credit Max Hawthorne)

Can one bone be used to identify a species?

When looking for possible culprits, I was able to consider both the location and the strata where the fossil was discovered. Without that to aid me, I would have literally been doing the needle-in-a-haystack thing. Luckily, I knew that the fossil was found in Russia, which brought to mind two recent pliosaur discoveries, Makhaira rossica and Luskhan itilensis. However, both of these animals lived during the upper Hauterivian (Lower Cretaceous), which rules them out. In fact, to the best of my knowledge, the Upper Albian stage is known for two macropredatory pliosaur species, K. queenslandicus and K. boyacensis. With no other likely contenders, that leads me to believe that my Russian pliosaur paddle bone did, indeed come from one of the two Kronosaurus species. If this is the case, it strongly suggests that, in addition to discoveries made in Queensland and New South Wales in Australia, as well as in Boyacá, Colombia, the genus also prowled the seas of what is present-day Russian, making its distribution even more cosmopolitan than has been previously thought.

How big was it? Putting meat on the bones.

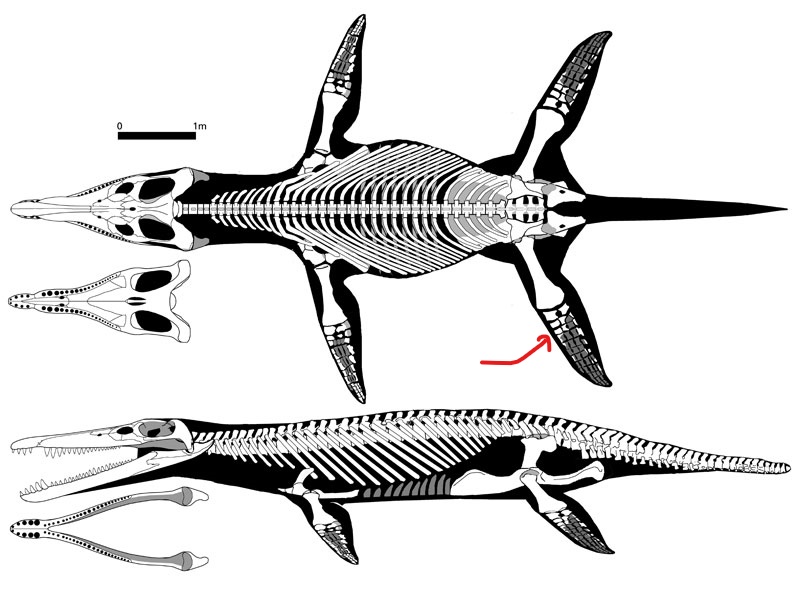

Calculating the approximate size of an extinct animal using a single bone is an enormous challenge. Especially, when so little fossil material exists to begin with. Still, science is often based on assumptions. In this instance, I am assuming that the paddle bone is as it was estimated to be – a metapodial from a large pliosauromorph (of this, I am reasonably sure), and that it did, indeed, come from one of the two known genera of Kronosaurus (of that, I’m fairly sure). To calculate the size, I am basing my estimates on the most detailed, up to date, and anatomically accurate skeletal drawing of K. queenslandicus that I could get my hands on.

By measuring metapodial #1 in the rear paddle (which, for the record, looks very similar to the actual fossil, at least in terms of the illustration) and comparing that to the skeleton’s LOA (length overall) I was able to calculate a ratio of 115 to 1, and with the fossil metapodial measuring 3.5” was able to calculate the specimen’s total skeletal LOA at approximately 33.5 feet. Fleshed, the animal would probably have been about 35 feet in length with a mass of around 13 tons.

Conservative estimates – could it have been even bigger?

Although some have suggested, (including the dealer from whom I purchased the specimen) that the paddle bone is actually from a front flipper, in the interest of being conservative, I have focused my calculations on the rear flipper. Firstly, it seems to match the skeletal reconstruction and, secondly, most paleontologists have an annoying tendency of being overly conservative. The odds are that it was from the rear paddle and, if my estimates are correct, my Russian pliosaur falls in line with current size estimates for the Kronosaurus genus (note: if it is from one of the two species, it being found in Russia is still a momentous discovery). However, I will issue a few caveats. The first is that if it was from the front paddle instead (and if all other estimates and assumptions turn out to be true), where the metapodial is smaller, the animal could have been 20-25% larger – perhaps as much as 42-43 feet. The second is that the fossilized bone appears to have come from a young and healthy animal. The bone shows no evidence of arthritic changes and the synovial joint portion on either side is perfectly smooth, with no sign of deterioration of the cartilage that was there 100 million years ago. This suggests that the metapodial’s previous owner was still a relatively young animal, and with reptiles growing all their lives, could have gotten even bigger over time. Regardless, as it stands, a 35-foot super predator capable of biting a great white shark in half is still nothing to sneeze at.

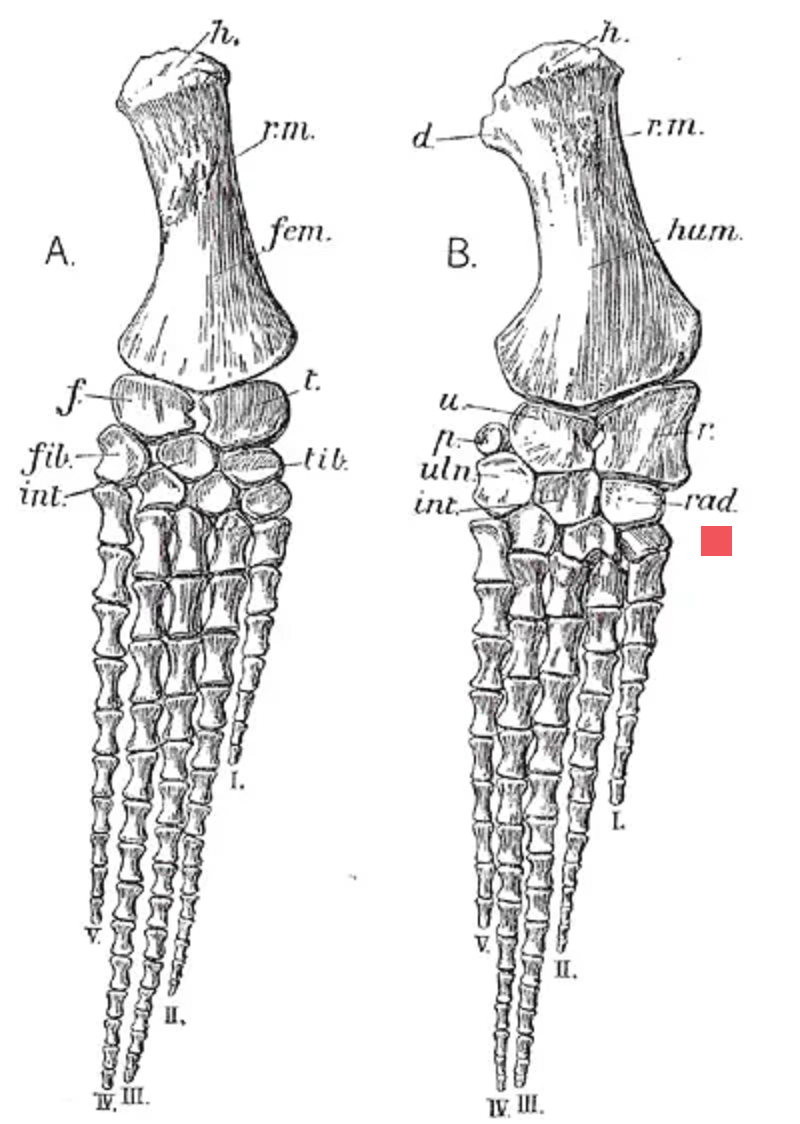

UPDATE (11/2/2021): after doing additional research, including speaking to a Russian paleontologist who happens to be a pliosaur specialist, I have confirmed that the bone in question is, indeed, a front forelimb mesopodial (carpal bone). It is an ulnare, to be exact. See the paleontology illustration below (bone is from a fore-flipper, marked in red). The oblong bone marked “uln.” is unmistakable.

With this new information, I was able to reassess the theoretical size of the animal in question. Going by the Kronosaurus skeleton recreation above, the animal’s skeletal length comes out at around 38 feet. However, that reconstruction is highly speculative, as only the bones indicated in dark gray have been found. This makes proper proportions difficult, and the results prone to myriad errors. If I go by established plesiosaur paddle reconstructions based on actual fossils, however, we end up with a paddle that is 82 inches in length (6’10”) and a skull-only length of 105.9″ (8’10”). Using known proportions for Kronosaurus, which is typically a head-to-body ration of 1:4.35, that gives us an animal with a skeletal length of ~38’5″ and a total (fleshed) length of ~42 feet. Scaled up from a 35-foot specimen weighing 13 short tons, we could be look at a behemoth in 23-24-ton range.

I hope you enjoyed this blog post. Special thanks to Valentin Fischer and Paul de la Salle for their expert advice and invaluable insight. If you haven’t already, please take a moment to visit the home page and sign up for my monthly newsletter. Also, if you’re not up-to-date on the latest Kronos Rising novels, feel free to download an excerpt here on the site.

Sincerely,

Max Hawthorne