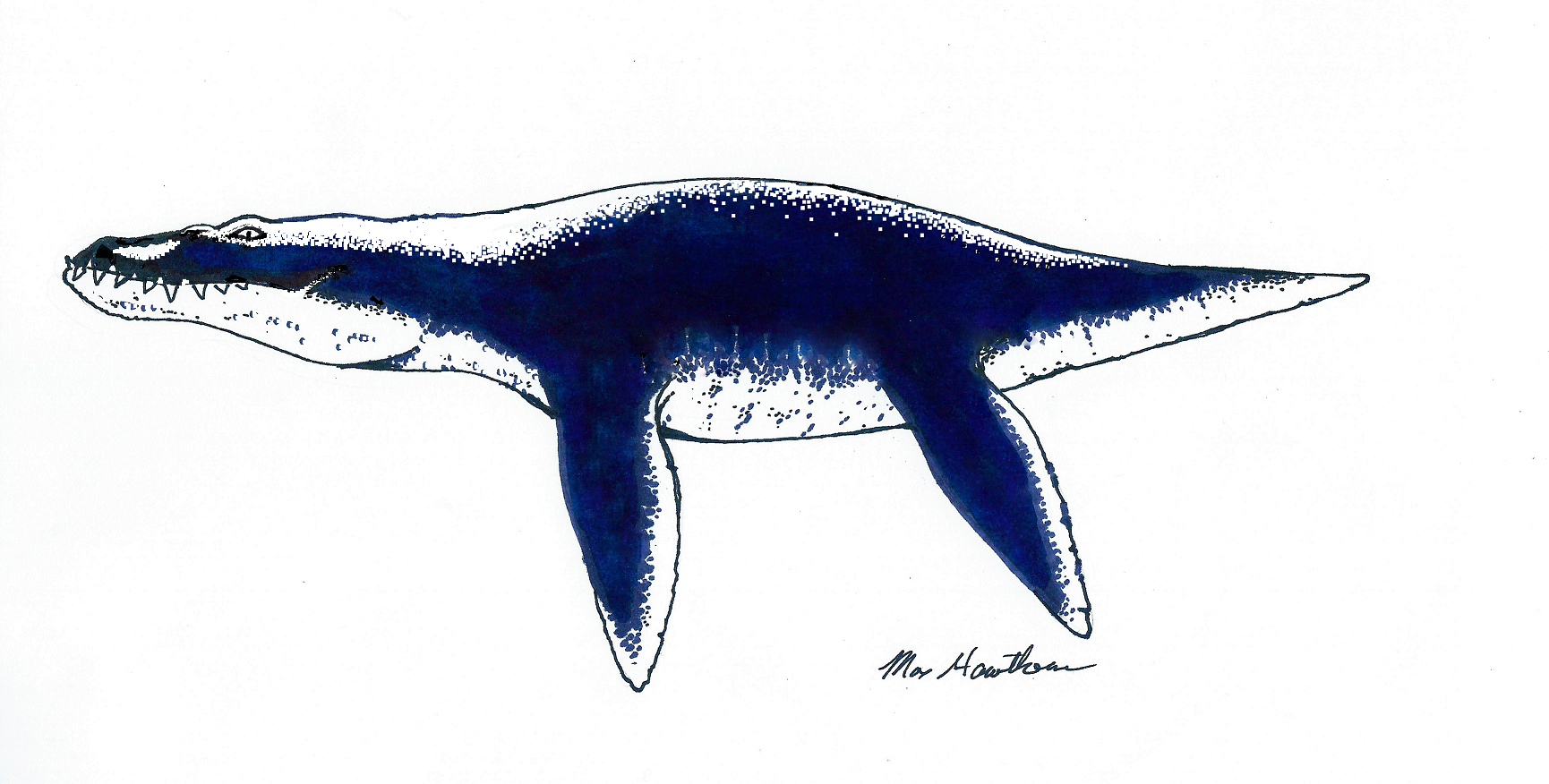

When it comes to figuring out what sort of pliosaur color patterns existed back in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, it’s pretty much anybody’s game. Heck, we don’t even know for sure what the skin texture of these macropredators was like, let alone what hues they presented. (probably something along cetacean lines but with tight, streamlined scales would be my guess). Were they plain-gray in color like modern sperm whales? Did they use counter-shading, light below and dark above, like many large sharks? Did they have Orca-like patterns, or stripes or bands or even polka dots? Were the males a different and more striking color than the females for mating purposes?

All legitimate possibilities (other than the polka dots, one would hope), and we will most likely never know. One type of pattern I think is distinctly possible would be a hunting-geared type of adaptive camouflage – an evolutionary attempt at mimicking the silhouette of the predator’s main prey item. This would be especially useful if the prey in question was swift and agile and required the hunter to get in close in the hopes of taking it by surprise.

A recent conversation with talented paleo-artist Tone Hitchock (who is in the middle of crafting a life-sized 8-meter pliosaur sculpture for a museum sponsor and who has posted some amazing potential pliosaur color patterns on social media) inspired me to explore this topic further. I reasoned that many pliosaurs, such as Kronosaurus queenslandicus, regularly fed upon plesiosaurs and elasmosaurs. They would use their mighty jaws, lined with fangs the size of bananas, to seize and crush the more delicate fish-eater’s skull before it could retaliate with a nasty bite. This is confirmed by fossil evidence.

Of course, plesiosaurs were, themselves, fleet of foot (make that flipper), and would hardly sit still if they saw something the size of a box car with teeth coming at them. Keeping that in mind, I developed a skin color pattern that I felt would allow a large pliosaur to mimic the overall outline of its prey. By creating the appearance of another plesiosaur – at least at a distance – it might allow the huge carnivore to get close enough that it could deliver a strike before its unfortunate victim was alerted and could dodge it and sprint to safety.

These were my end results. In both versions, the overall body mass and even the fins seem to be reduced by the lighter ventral portions. If you look close, you can also see a light area on each pliosaur’s muzzle that’s designed to imitate an “eye”. I’m sure neither of these designs are spectacular enough for someone as discerning as Tone’s sponsors (although the second version does have a nice “Apache thing” going on), but they’re certainly feasible/natural. If you squint, they actually do a nice good job of creating the silhouette of a long-necked plesiosaur from afar. I can just imagine a pod of Cryptoclidus peering through the gloom, alarmed as something suddenly passes by, some 50 yards off. At that distance, however, the prowling Pliosaurus might well be interpreted as just another member of the pod. The long-necked plesiosaurs would relax. That is, until their natural predator spun toward them at high speed and charged, its monstrous jaws agape and dinner on its mind.

It’s a “colorful” tale, don’t you think? 😉

-Max Hawthorne